When Poverty and Insecurity Push Education Out of Reach for Our Precious Nigeria Children

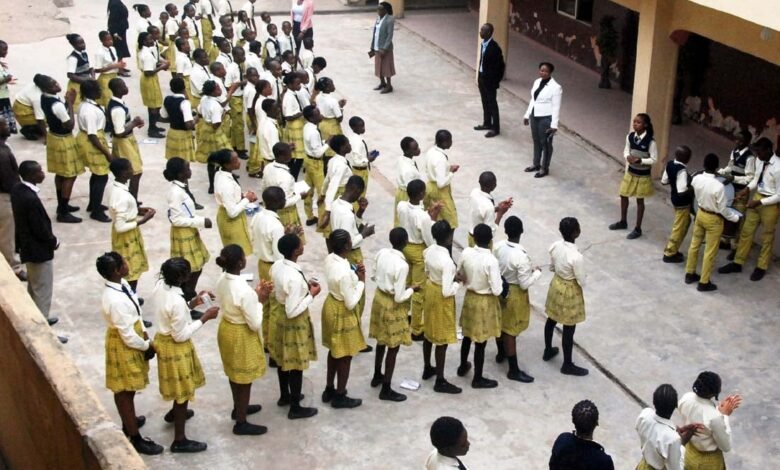

As a new academic session begins across Nigeria, thousands of children are not returning to school. For many families, especially in the country’s northern regions, education has become a distant concern, overshadowed by poverty, displacement, and persistent insecurity. While school resumption is typically a time of renewal and optimism, this year it has instead revived deep fears among parents who must weigh the value of education against the daily realities of survival and safety.

Displacement and survival over schooling

The impact of insecurity is most visible among families displaced by banditry and violent attacks across northern states. Many internally displaced persons now living in host communities in Kaduna, Niger, and neighboring states say they can barely afford food, leaving no resources for school fees, uniforms, or transport.

For these families, education is no longer a choice delayed, but a necessity abandoned.

Parents recount fleeing their villages after attacks in Katsina, Niger, and Kaduna states, arriving in unfamiliar communities with little support. Some rely on charity to enroll children in informal religious schools, while others say none of their children attend school at all.

Their experiences reflect a broader pattern. When insecurity strips families of livelihoods, education becomes one of the first casualties.

Schools as targets, not sanctuaries

Beyond poverty, fear remains a powerful deterrent. Across Northern Nigeria, schools have increasingly become targets of attacks, abductions, and intimidation.

In December 2025 alone, escalating violence forced the federal government to close 41 Unity Schools nationwide. Governors in Kwara, Plateau, Niger, Benue, and Katsina also suspended academic activities following security threats.

Public anxiety peaked after bandits abducted 215 students and 12 teachers from St. Mary’s School in Niger State. Just days earlier, 26 schoolgirls were kidnapped from a government secondary school in Kebbi State.

These incidents reinforced a painful reality for many parents: schools, once considered safe spaces, are now seen as high-risk environments.

Education experts warn that this shift in perception may have long-term consequences. When parents lose confidence in the safety of schools, enrollment drops, attendance becomes irregular, and learning outcomes suffer.

The scale of vulnerability

Data from the National Plan on Financing Safe Schools paints a stark picture of the risks facing education infrastructure in the North.

More than 42,000 primary and secondary schools across Northern Nigeria lack perimeter fencing. Over 4,200 secondary schools and nearly 39,000 primary schools remain unfenced, leaving them exposed to attacks.

States such as Kano, Bauchi, Niger, Katsina, Benue, Plateau, and Jigawa account for a significant share of these vulnerable schools. In many rural communities, schools lack not only fencing, but also security personnel, lighting, water, and basic facilities.

Experts note that insecurity thrives where institutions are weak and poorly protected.

Government responses and their limits

Federal and state governments have reiterated their commitment to securing schools. Several northern states, including Sokoto and Kebbi, say they have activated security arrangements around public schools as students return.

At the federal level, authorities point to initiatives such as the Safe School Programme and increased collaboration with security agencies. Officials maintain that protecting students remains a national priority.

However, educators and security analysts argue that current measures are uneven and insufficient. They stress the need for better intelligence sharing, stronger community policing, and tailored security strategies that reflect the vulnerability of each school.

Some experts warn that repeated school closures, while intended as a safety measure, may unintentionally empower criminal groups and deepen learning losses.

Poverty, cost, and unequal access

Even outside conflict zones, economic pressure continues to limit access to education. Rising school fees, transportation costs, and inflation have strained households across the country.

In the Federal Capital Territory and other urban areas, parents acknowledge that private school fees have increased sharply. School owners cite higher salaries, electricity costs, security expenses, and learning materials as unavoidable drivers of these increases.

While some parents accept higher fees in exchange for better supervision and learning standards, others are priced out entirely, pushing children into overcrowded public schools or out of the system altogether.

Students themselves often express optimism about returning to school, focusing on friendships, routine, and personal goals. Yet for many, that optimism depends entirely on whether their families can afford to keep them enrolled.

A broader child welfare crisis

Education challenges are unfolding within a wider child welfare emergency. At a recent UNICEF and Nigerian Guild of Editors symposium, stakeholders warned that Nigeria’s child indicators are deteriorating across education, health, nutrition, water access, and protection.

Nigeria has the world’s highest number of out-of-school children. Millions remain unvaccinated, face acute malnutrition, or lack access to safe water and sanitation. Regional disparities are stark, with some northern states recording extremely low access to basic services.

UNICEF officials emphasized that progress is possible, but only if reforms are accelerated and investments guided by evidence.

Government representatives highlighted ongoing programmes targeting out-of-school children, adolescent girls’ education, women’s economic empowerment, and menstrual health, noting that these efforts require sustained funding and coordination.

The role of media and accountability

Media leaders and child rights advocates argue that reporting on insecurity and education must move beyond episodic headlines. They call for deeper analysis that examines policy implementation, funding gaps, and lived experiences of children and families.

They also stress that indiscriminate school closures, misinformation, and delayed responses worsen public fear and undermine trust.

Journalists, civil society, development partners, and government agencies, they argue, must work together to ensure that child protection policies move from paper to practice.

A future at stake

With more than half of Nigeria’s population under the age of 18, the consequences of disrupted education extend far beyond individual families. Each child denied learning today represents lost potential tomorrow.

Poverty and insecurity are not abstract policy challenges. They shape daily decisions in households across Nigeria, forcing parents to choose between safety, food, and education.

As the school year unfolds, the central question remains unresolved: how can Nigeria protect its children, keep schools open and safe, and ensure that no child is denied an education simply because of where they were born or the violence they fled?

For many families, the answer cannot come soon enough.