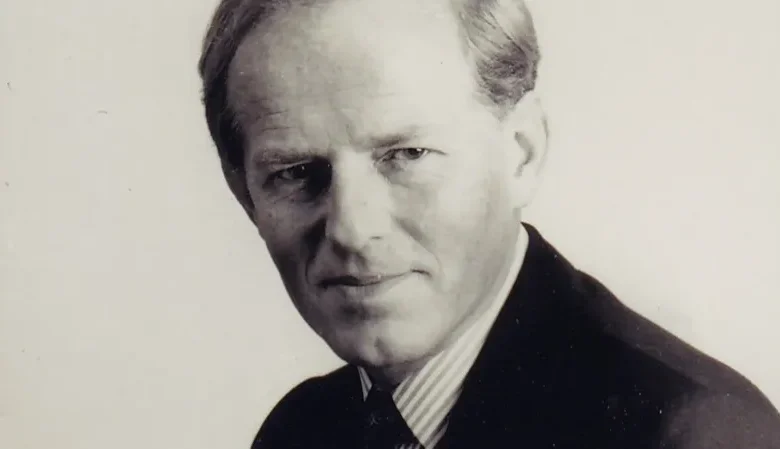

“My Father Abused 130 Boys”: Daughter of Church-Linked Serial Abuser Speaks Publicly for the First Time

The daughter of John Smyth QC, the man believed to be the most prolific serial abuser associated with the Church of England, has spoken publicly about the devastating moment she learned the full truth of her father’s crimes.

Fiona Rugg, 47, said discovering that her father had subjected around 130 boys and young men to extreme physical and sexual abuse was “shocking and horrifying”. Smyth, a barrister and prominent Christian charity chairman, died in 2018 before he could be prosecuted.

The abuse took place mainly in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Under the guise of spiritual discipline, Smyth beat his victims naked with canes, inflicting severe injuries that left some bleeding heavily. He framed the violence as punishment and repentance for supposed moral failings, using his religious authority to control and silence those in his care.

Speaking to the BBC for the first time, Ms Rugg said coming to terms with her father’s actions has been a long and painful process, marked by what she describes as “shame by association”.

“I know rationally that I am not to blame,” she said. “But you still feel guilt that your father could do this to someone. He was unrepentant, and that makes it harder.”

She said much of Smyth’s life was defined by deception and concealment, aided by others who chose silence over accountability.

“So much of how he got away with it was cover-up,” she said. “I want to do the opposite of that. I want things brought into the light.”

A 2024 independent inquiry, known as the Makin Review, concluded that the Church of England’s response to allegations against Smyth amounted to a cover-up. The report found that senior figures failed to alert police despite being aware of the seriousness of the abuse. One cleric admitted they feared public disclosure would damage the church’s work.

Ms Rugg said learning the full extent of her father’s actions, though deeply distressing, has been part of her healing.

“I have forgiven him,” she said. “That does not make it right, and it does not erase the pain. It does not lessen the horror of what he did. But I am no longer held by shame.”

She added, “There was nothing from him that resembled remorse. So I am sorry on behalf of my father for what he did to those boys.”

She described her childhood as dominated by fear and emotional instability. Smyth, she said, was volatile and unpredictable at home, leaving her constantly alert to shifts in his mood.

“I was afraid of him for as long as I can remember,” she said. “He was angry, unkind, and frightening. You learned to walk on eggshells.”

At the same time, she watched others admire and praise him.

“What confused me was seeing how adored he was,” she said. “I wanted to get away from him, yet people treated him as if he were wonderful. As a child, you conclude that he must be right and you must be the problem.”

While Smyth socialised openly with boys and young men, Ms Rugg recalled being told to stay away, dismissed as an inconvenience. She said her family life revolved entirely around her father’s authority.

Access to Winchester College in the early 1970s through the school’s Christian Union allowed Smyth to begin abusing pupils, often after inviting them to his home. An internal investigation by the Iwerne Trust uncovered the abuse in 1982, describing it as “prolific, brutal and horrific”. Records showed that eight boys alone endured a combined total of 14,000 lashes.

Despite this, the authorities were not informed. Instead, senior evangelical figures arranged for Smyth to leave the country quietly.

In 1984, the family relocated to Zimbabwe. Ms Rugg said the move was presented as a noble sacrifice, with her father abandoning a successful legal career to pursue missionary work. In reality, she said, the pattern of abuse continued. Smyth established Christian camps where he enforced nudity and carried out beatings.

In 1985, a 16-year-old boy, Guide Nyachuru, was found dead at one of the camps shortly after arriving. Smyth was charged with manslaughter, but the case collapsed.

When Ms Rugg returned to England at 18, she began to sense something was deeply wrong. Mentioning her father’s name, she noticed people’s reactions shift to silence or discomfort.

“There was no warmth,” she said. “Just a shadow passing across their faces.”

When she confronted her father with rumours of abuse, his response confirmed her fears.

“He flew into a blind rage,” she said. “He accused me of disloyalty. It was so extreme that I knew then there was truth behind the rumours.”

Public exposure came in 2017, when a Channel 4 investigation revealed the scale of Smyth’s crimes. Ms Rugg said seeing her father’s face on the news was devastating.

“These were people’s sons,” she said. “Lives ruined. I have a son myself. I had no idea the abuse was so extensive, but it suddenly made sense.”

In 2018, Hampshire Police issued a summons for Smyth to return to the UK for questioning, warning of extradition if he refused. He died of heart failure eight days later, aged 77, before any interview could take place.

Now, Ms Rugg says she can speak about her father without hatred and feels a measure of peace.

“If you face the truth, you can heal,” she said. “There are still moments of pain, but I no longer feel that knot inside. What he did is not mine to carry.”

She added, “It has gone from something imposed on me to something I choose how to live with.”

A two-part Channel 4 documentary, See No Evil, examines John Smyth’s history of abuse and the institutional failures that allowed it to continue for decades.