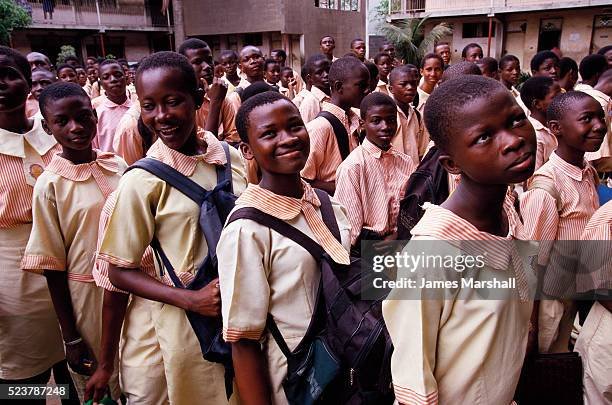

Between School and Survival: Why Many Girls in Oyo State Still Miss Classes

On a weekday morning in Olodo, a semi-urban community on the outskirts of Ibadan, 15-year-old Rihanat Kolawole should have been seated in her classroom. Instead, she was weaving through a dusty market, delivering peppers for her mother during school hours.

Rihanat is an SS1 student at Community High School, Alakia Isebo. Her mother is a petty trader, her father a motor park messenger. Their combined income barely sustains the household. Paying school-related costs often comes second to food and rent.

“I have had to stay at home for a whole year before moving to the next class because there was no money,” she said. “I just want to finish school. I don’t want to stop.”

Her experience reflects a quiet but persistent reality across Oyo State, where many girls miss classes not because they lack interest in learning, but because poverty, domestic responsibilities, and systemic gaps repeatedly interrupt their education.

Poverty’s daily pull on education

For families struggling to survive, the immediate value of a daughter’s labour often outweighs the long-term promise of schooling. Girls are sent to markets, roadside stalls, or kept at home to care for siblings. Over time, missed lessons accumulate into repeated classes, delayed promotions, and eventual withdrawal from school.

Twelve-year-old Rokibat Ayoade, a Primary Five pupil in Olodo, attends school only every other day. Each evening, she sells pap at a busy junction to support her family of eight. Her parents work long hours, but their income remains uncertain.

“My mother tries her best, but it is not enough,” Rokibat said.

Such arrangements, while born of necessity, leave girls perpetually behind their peers, struggling to keep pace academically while carrying adult responsibilities.

The hidden cost of “free” education

Although public education in Oyo State is officially free at the basic level, the real cost of schooling remains a significant barrier. According to the State of Girl Child Education report by the Onelife Initiative, supported by the Malala Fund, families may spend as much as ₦89,200 per term on uniforms, books, transport, and other supplies for one girl. That amounts to over ₦267,000 per academic session.

For low-income households, these costs are prohibitive. They discourage enrolment, increase absenteeism, and make retention difficult, especially for girls, who are often deprioritised when resources are scarce.

Gender gaps and social pressures

Globally, gender parity in education remains elusive. UNICEF data shows that only 49 per cent of countries have achieved parity at the primary level. The gap widens significantly at secondary education.

In Oyo State, poverty intersects with entrenched social practices. Data from the 2021 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey indicates that 13.2 per cent of girls are married before age 18. Early pregnancy, domestic labour, and care duties further reduce girls’ chances of completing school.

Education experts note that while Oyo performs better than many northern states, silent inequalities persist beneath the surface.

Menstrual health and school absenteeism

Menstrual hygiene remains a less visible but significant contributor to absenteeism. Many girls lack access to sanitary pads, private toilets, or accurate information. As a result, some stay home during menstruation due to fear, pain, shame, or stigma.

Theresa Moses, convener of the Pad Me a Girl Initiative, said many girls resort to unsafe alternatives such as cloth or tissue.

“Menstruation becomes a monthly crisis,” she said. “It is not just a health issue. It is an education and human rights issue.”

Poor Water, Sanitation and Hygiene facilities compound the problem. UNICEF and education partners have linked the absence of clean, private toilets to increased dropout rates among adolescent girls.

Teachers confirm the impact. At Islamic Mission School in Ona Ara, enrolment reportedly rose after UNICEF-supported toilets were constructed in 2023, transforming the school environment and improving attendance.

Policy gaps and reintegration challenges

Beyond poverty, policy weaknesses continue to push girls out of school. Tunde Aremu of Plan International Nigeria argues that social norms are often overstated, masking deeper systemic failures.

“Where education is genuinely free, parents send their daughters to school,” he said.

He identified a lack of clear policies mandating the re-admission of pregnant girls as a major barrier. Stigma, often reinforced within schools, discourages many young mothers from returning to class, even when they are willing.

Community and civil society interventions

Despite these challenges, interventions by civil society groups offer some relief. In Ibadan, the Ineza Care Foundation has paid examination fees and provided learning materials to hundreds of girls who would otherwise be unable to sit key exams.

Teachers describe heartbreaking scenes of students attending classes until the final day, knowing they cannot afford to register for examinations. Those who miss exams are often sent to learn trades, a transition that sometimes leads to early pregnancies or abandonment of both education and skills training.

Educators emphasise that teacher support and school-based counselling can make a decisive difference, especially for girls from unstable homes.

Government response and remaining gaps

The Oyo State Government says it is working to remove financial and social barriers through the Universal Basic Education framework, which eliminates fees and levies in public schools and provides free textbooks.

According to the Commissioner for Women Affairs and Social Inclusion, Toyin Balogun, the state also runs targeted interventions, including scholarships, study grants, back-to-school material distributions, and re-enrolment campaigns under the BESDA programme.

Gender-responsive initiatives, including menstrual hygiene education and WASH improvements, are being incorporated into the 2026 state budget. Several gender-focused policies, including menstrual hygiene and anti-trafficking frameworks, are expected to be implemented by 2026.

However, the commissioner acknowledged gaps, particularly the absence of a comprehensive policy addressing teenage pregnancy and systematic school reintegration for young mothers. Enforcement of child protection laws also remains uneven in some communities.

An unfinished journey

For girls like Rihanat and Rokibat, education remains a fragile pursuit, constantly threatened by hunger, unpaid costs, and family obligations. Their determination persists, but resilience alone cannot close systemic gaps.

Oyo State’s experience highlights a broader truth. Keeping girls in school requires more than free tuition. It demands sustained investment, functional policies, safe school environments, and social support systems that recognise the realities of poverty.

Until those pieces align, many girls will continue to stand at the crossroads between school and survival, carrying ambitions that depend not on ability or effort, but on whether support arrives in time.

Source of image: Getty Images