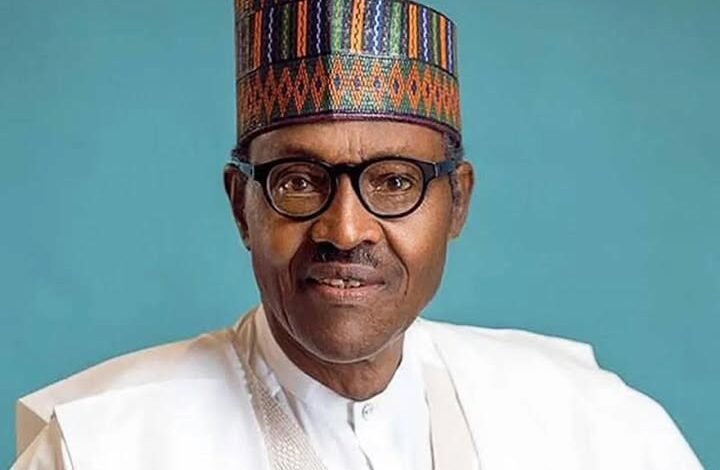

Beyond the Death of PMB: Building a Nigeria Our Children Can Trust

Since the news broke of our former president’s passing, I’ve been reflecting, not to offer political commentary, but to prepare my son for this moment.

Nigeria is 65 years old, older than Singapore. Yet even now, our former presidents must seek medical treatment abroad. How do I explain to my son that the former president of the world’s most populous Black nation died in a foreign hospital, while most Nigerians could never dream of such care?

One of his aides, Mr. Femi Adesina made a shocking admission on Channels TV: that he “would have been long gone” if he hadn’t gone abroad for treatment. That statement, though dressed as loyalty, is a damning verdict on our health system, and, by extension, our leadership. It confirms what we all know but rarely say plainly: that Nigeria is a medical death trap for its citizens.

How can any leader or their spokesperson say such a thing without flinching? With that statement, are we to assume that all those Nigerians who couldn’t travel abroad were simply fated to die? Millions of our people are already “long gone” because they lacked the privilege of foreign healthcare. That’s not just insensitive, it’s cruelly detached.

To make it worse, reports say the late former president was in the same foreign hospital as another former Nigerian leader. What does that tell us? That not even in death, or illness, can they rely on the system they once presided over.

It baffles me that the King of England uses the NHS, the President of the United States is treated in government hospitals, yet our own leaders cannot step into the hospitals their administrations funded. If their lives are not “safe” in Nigerian hospitals, what about the rest of us?

Now that we all agree the system is broken, I ask: what did the late president do to fix it, especially in his second coming, when he had a full eight years in office? If he had suffered these limitations even before becoming president, wouldn’t that personal experience have stirred him to build a world-class health system at home?

He died in a foreign hospital after eight years in power. That’s not just unfortunate. That’s unacceptable.

Transformation Is Possible, and Fast Take Singapore. In 1965, it was a struggling post-colonial outpost. Within about 25–30 years, under Lee Kuan Yew’s leadership, it became a high-income nation with GDP per capita skyrocketing from US $1,240 to over $18,000 by 1990. Today, it’s a global hub, proving that the journey from developing to developed can be swift when led by vision, discipline, and public investment.

And this problem isn’t new. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, when airports were shut and foreign hospitals were inaccessible, several prominent Nigerians died. We thought that would be the wake-up call, that leaders would finally invest in building resilient healthcare systems. But no lesson was learned.

How do I explain this to my son?

How do I tell him that leaders of countries with once-similar colonial histories, like India, now a global tech hub, or China, now the world’s second-largest economy are more likely to die in their own countries than ours?

How do I explain that Nelson Mandela died in a South African hospital, Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore, and Jimmy Carter in the U.S. and Queen Elizabeth in the UK, but our own leaders cannot trust the hospitals in their homeland?

It’s not just strange. It’s tragic. And worse, we’re accepting it as normal.

Consider the scale of this dysfunction:

Nigeria loses $1–2 billion annually to medical tourism, funds that could build state-of-the-art hospitals here at home.

Our doctor-to-patient ratio is 1:2,500, far below the WHO’s 1:600 benchmark.

Nearly 50% of licensed Nigerian doctors have emigrated. That brain drain has devastated our healthcare capacity.

When leaders run abroad for care, it sends a clear message: “Our system is not good enough.” That mindset normalizes neglect. It entrenches inequality. And it weakens national pride.

Here’s what I tell my son:

A leader’s health is a public concern, not a private privilege.

National institutions must serve all citizens, not just the elite.

We must never accept medical exile as normal, we must demand better.

You must be part of the solution, not just a witness to national decline.

This moment is bigger than one death. It’s about the kind of country we’re building. A country that imports everything, medicines, doctors, systems, solutions—but refuses to invest in itself.

My son must know: this is not how things should be done. This is not normal. And it is not sustainable. For Nigeria, today’s wake-up call is clear: we can choose better. We can build hospitals, schools, industries, and infrastructure, faster and smarter, if we commit. Our past doesn’t define us; our choices do and those choices are in our hands.

Do have an INSPIRED week ahead with the family